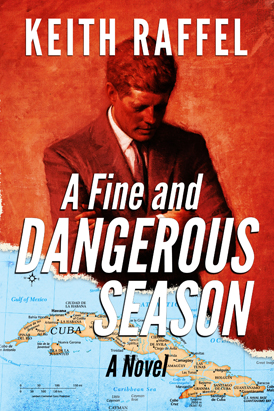

A Fine and Dangerous Season

Behind the Book

Who knew that future president John F. Kennedy had

spent the fall quarter of 1940 at Stanford Business School in my hometown of Palo Alto, California? Well, once I

found out, I asked myself the two-word question that all thriller authors ask: “What if?” What if

during his time at Stanford, JFK becomes fast friends with someone from a completely different background who is

Jewish, not Catholic, San Franciscan rather than Bostonian, with a famous left-wing father, not a buccaneering

capitalist one? And what if JFK and this fictitious character, Nate Michaels, have a falling out? Kicking around

these ideas with college pal Rick Wolff, he asked the best “what if” of all: What if JFK needs this

guy’s help 22 years later during the Cuban

Missile Crisis?

In the fall of 1940, Kennedy was just killing time at Stanford. He’d already graduated from Harvard

College. His book Why England Slept (based on his

senior thesis) had hit the bestseller lists in the spring. He figured war was coming, and he’d enlist. His

father, the formidable Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., the American ambassador to Great Britain, wanted him to go to

Yale Law School. But his older brother’s college roommate had expounded on two major differences between

Harvard and Stanford--the weather and co-education. That was argument enough to make JFK beat it to Palo Alto as

a special student at the business school. What better place to hang out?

I could empathize with “Jack” Kennedy. After graduating from college, I was trying to figure out

what to do as well. To get far away from my hometown (which, after all, is Palo Alto), I headed over to England

to study history. Good decision. I am just now realizing that what I loved about studying history is the same

thing I love about composing thrillers. In both, I get to look at how people react to an emergency, a time of

high drama, and how they show courage--or not. That’s a theme I explore in my new e-book, A Fine and

Dangerous Season. Using primary research whenever possible, I try to fit the events of the novel into the

interstices of the historical record.

As a first step, I drove by 624 Mayfield on campus where Kennedy lived in a guest house that he rented for $60

per month. (The house is long gone.) JFK used to head down to Los Angeles, too. In his 1980 memoir, Straight

Shooting, actor Robert Stack of The

Untouchables fame describes how JFK took advantage of Stack’s “little pad” on Whitley

Terrace for rendezvous with various Hollywood starlets. At the Palo Alto Library, I found old menus from

JFK’s favorite hangout, L’Omelette. The prices seemed reasonable enough--a quarter for a martini and

six bits for a French lamb chop dinner! I discovered JFK’s favorite courses at Stanford weren’t

business classes at all, but--no surprise--courses on politics and international relations. From the archives of

the student newspaper, The Stanford Daily, I learned that the closest call in Stanford’s 1940 undefeated

football season came against the University of California, Los Angeles, where a fellow named Jackie Robinson almost beat the

Stanford team single-handed.

The bar at L’Omelette

Back at the Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston, I found a teasing and witty letter from Kennedy’s

Stanford girlfriend Harriet “Flip” Price, who chided, “You wouldn’t exactly win a prize

for the world’s best correspondent.” I got the biggest kick of all when I came across the schedule

of movies at the Stanford Theatre--which, amazingly enough, is still

showing great films from the 1940s in downtown Palo Alto. In one scene of my novel, set on a Saturday night in

October 1940, my man Nate and his girlfriend eat popcorn and hold greasy hands while the movie showing is The Quarterback. Wayne Morris plays twins, one a star

football

player without too much upstairs and the other an egghead studying to be a professor. Inevitably, both loved the

same girl, an oblique metaphor to what was happening in the “real life” laid out in my book.

Now, how was I going to find a role for Nate Michaels in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis? I remembered from a

college course that John Scali, an ABC News

correspondent, had opened a back channel during the crisis with a known KGB agent in Washington, D.C. In the

history of that crisis, as recounted in Fine and Dangerous, Scali was out and Nate was in. Back in the 1930s, a

Soviet consular official in San Francisco named Maxim Volkov had kept in touch with potential sympathizers like

Nate’s own father, a lawyer for the communist-leaning Longshoremen’s Union. Now, in the 1962 of my

novel, Volkov is head of the KGB in Washington, and JFK needs Nate to reach out to him to see if there is a way

to stop the headlong rush to nuclear war.

Doing the research on the Cuban Missile Crisis itself was much easier than the work I did on Stanford in 1940.

Few modern events have been more scrutinized by historians. With my preference for primary sources, I relied on

the book The

Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, some 500 pages of word-for-word

transcriptions of administration deliberations. That volume was co-edited by the late Ernest R. May, a great

historian and a favorite college professor of mine. Thanks to May’s work, characters in my own book could

use the same words they’d spoken in 1962. The only difference is that I place Nate in the room sitting

just behind JFK.

ExComm meeting at the White

House, October 29, 1962

I kept a book called Designing

Camelot: The Kennedy White House Restoration next to me as I wrote to ensure that I accurately described

White House rooms and the labyrinthine passages between them. It was much easier to get the architecture of the

KGB safe house right. As a model, I used the house on Swann Street NW in D.C. where I’d lived myself for

three years. Online, I found snapshots of the Steuart Motor car

dealership in the nation’s capital, where U2 reconnaissance photos of Soviet missiles in Cuba were

in fact analyzed. A person in the parish office at St. Stephens

Martyr Church told me there is a little brass plate on her building, noting that JFK frequently worshipped

there. One early reader of my manuscript suggested that the flight from Washington to San Francisco that Nate

catches at the end of the book seemed too short for half a century ago. Nope. Fifty-year-old flight schedules

show that 707s high-tailed it across the country faster than today’s advanced jetliners.

Oh yes, airplanes. In the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Nate frequently harks back to his years flying

bombers during World War II. When a B-17

Flying Fortress showed up at Moffett Field, just a few miles from my place in Palo Alto, my son and I

hustled down there and crawled through the plane. I spent more than my fair share of time squeezed into the

pilot’s seat and then came down to chat with B-17 veterans who recounted in unadorned words what it was

like on those long, cold flights from southeast England to targets in the German industrial heartland.

Certainly, the risk in writing a historical thriller is losing the thread of the plot and making readers feel

that they are being subjected to a graduate thesis. Believe me, I did try hard not to make that mistake with A

Fine and Dangerous Season. I promise I murdered lots of darlings. Still, the magic of writing this book

transported me right back to Palo Alto in 1940 and the White House in 1962. Even today, when driving down El

Camino Real in Palo Alto, I pass the corner where the old L’Omelette stood and see a hazy outline of John

F. Kennedy at the bar surrounded by a passel of admiring women.